| Art History

| Art HistoryConservation

Archaeology

In Memoriam | James R. McCredie

A Celebration of the Life and Career

of James R. McCredie

Bonna Wescoat

Director of Emory University and NYU Excavations at the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, Samothrace; Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Art History, Emory University

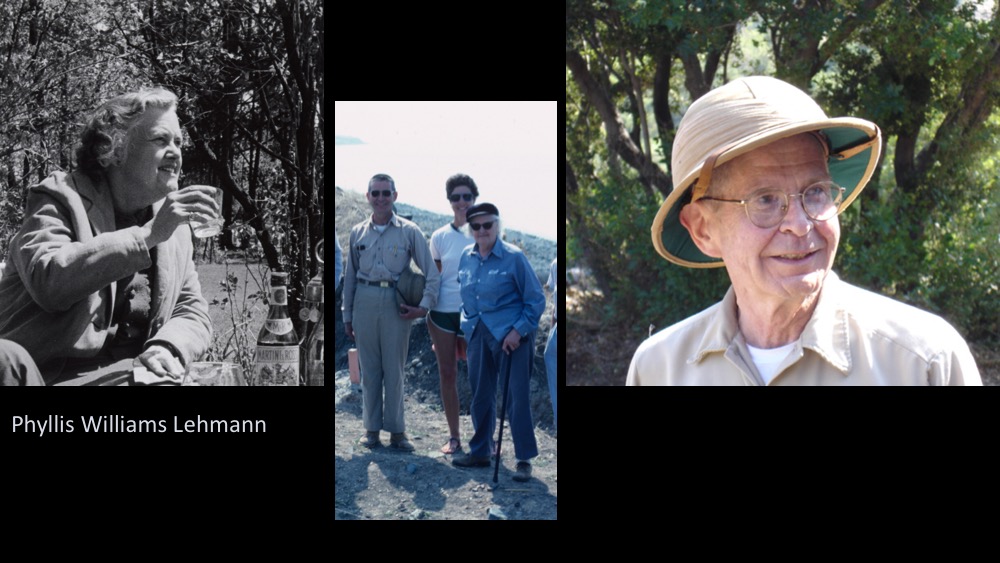

Chris, Mimsy, Meredeth and gathered friends, we have heard so many heart-felt words of praise and celebration for the remarkable life Jim McCredie shared with us; he influenced and transformed so many of our lives. I for one, can’t begin to imagine what my career, and more importantly my life, would have been like if Jim hadn’t—rather tentatively—agreed to Phyllis Lehmann’s request that I be allowed to come to Samothrace in 1977. It was an off season, so Jim said ok. We subsequently shared 30 summers on the island. One of many things I learned from Jim was the power of images and the preferred economy of words; in closing this afternoon’s tribute, I hope to celebrate Jim’s life as much with images as words. On the issue of sticking to my allotted time (knowing that Jim was more reliable than Greenwich), I hope I won’t be struck down by a thunderbolt; I plead indulgence in presenting the words of our Greek colleagues as well as my own.

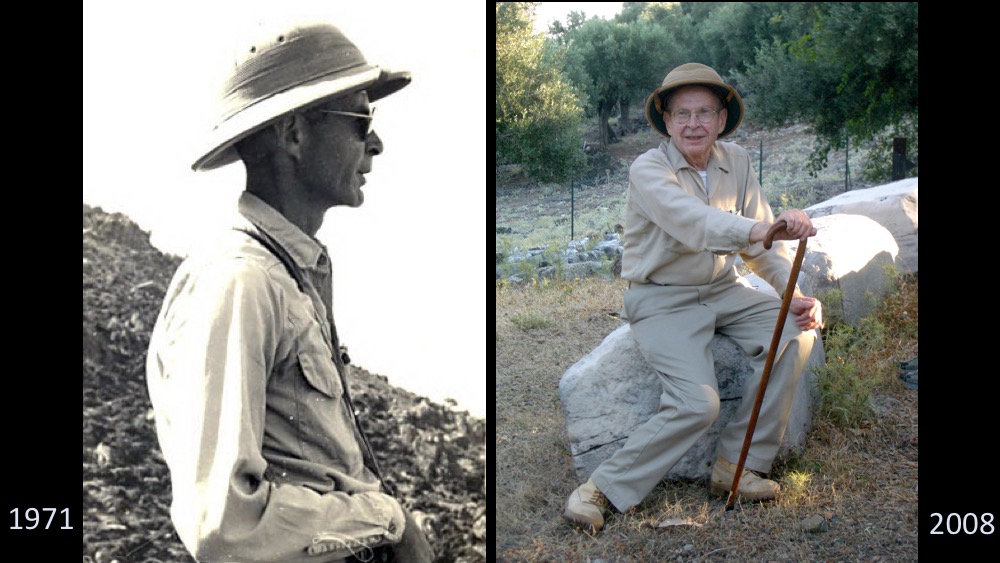

On the occasion of Jim’s retirement from the IFA in 2004, his long-time colleague, Evelyn Harrison, offered a tribute in which she characterized Jim as a lucky man, and indeed he was. But Jim was also the agent of his good fortune by being decisive and consistent. Early on, Jim identified what he wanted and valued, and he stuck to it. He was committed to his family, Greek archaeology, Samothrace and the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, the IFA, the American School, khaki attire, pith helmet, buzz-cut hair, ouzo hour at 8pm sharp, a signature recipe for brownies, a belief that Wagner’s Ring was the greatest opera, and the conviction that almost all culinary failings could be remedied with more butter.

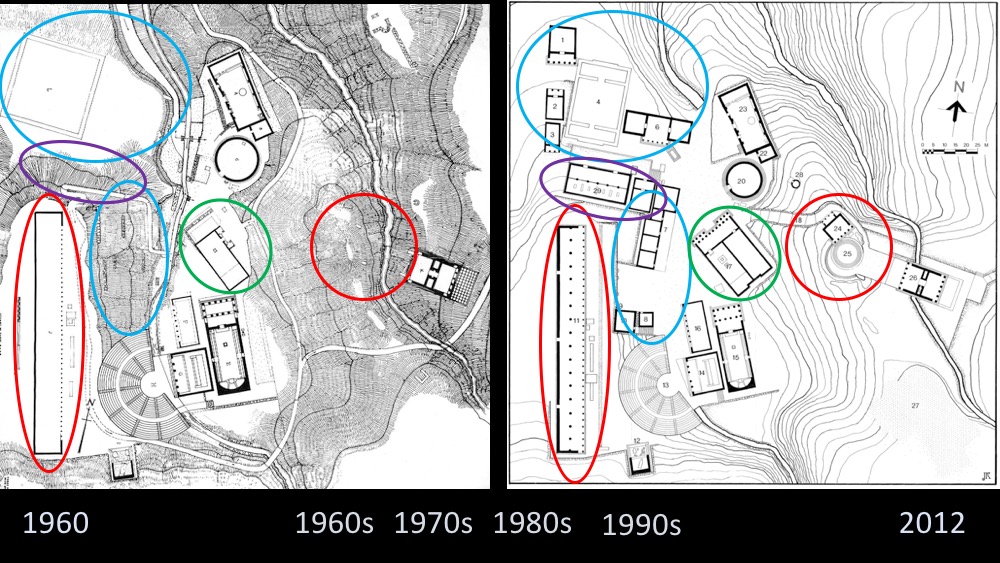

So, we have the paradox, in that while Jim looked virtually the same from his first to his last day on Samothrace, the Sanctuary of the Great Gods was utterly transformed by his deep knowledge and sharp intuition, decisively and consistently applied. In his 50 years as director, he doubled the number of known buildings in the Sanctuary, as we see here in the plan of the Sanctuary he inherited and the one he left to us.

In the 1960s, he articulated the Stoa and discovered the entrance complex on the Eastern Hill. The 1970s brought us the remarkable dining rooms on the western side of the valley, and the several buildings framing the western boundary. In the 1980s he added the remarkable Neorion, which housed an entire warship dedicated to the Great Gods, and in the 1990s he fundamentally up-ended our understanding of the heart of the Sanctuary with the discovery that the structure formerly known as the Temenos was a doubled-halled building with a splendid winged Ionic porch, which he named, with characteristic neutrality to function, the Hall of Choral Dancers.

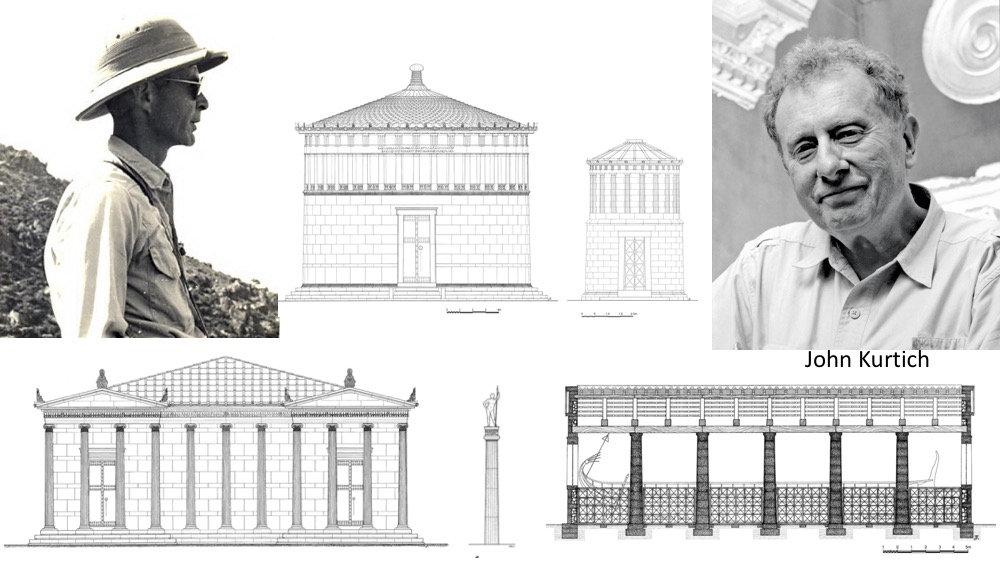

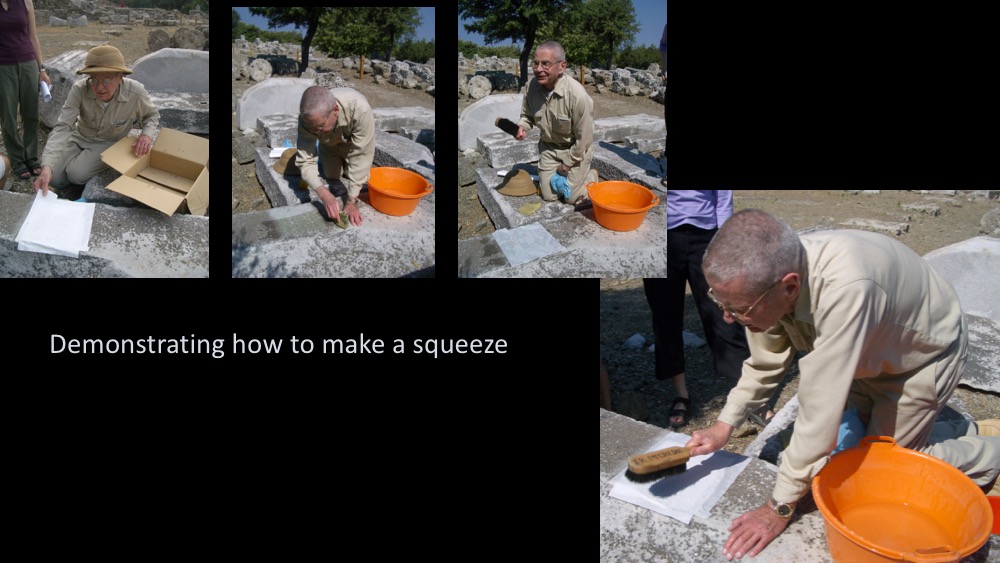

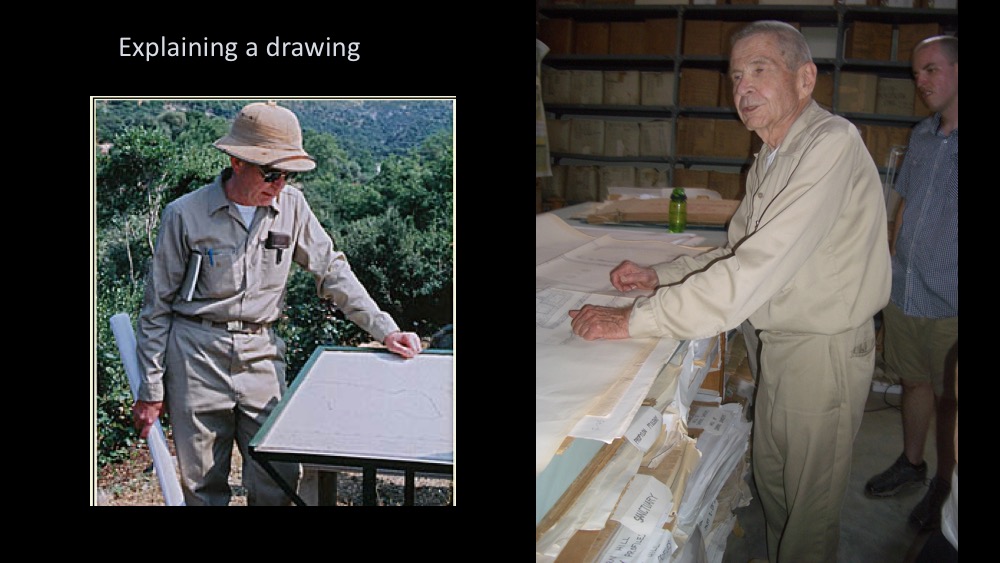

Every one of these Samothracian structures departs from the cannon of Greek architecture. Every one required not only minute analysis of detail but also creative exploration of ideas operating outside the standard toolbox. It was a pleasure to watch him at work, turning an object over in his hands, thinking through the options with Occam-like precision, making a decision, or holding back if he wasn’t convinced.

As a result, Jim gave us some of the most splendid buildings of the Hellenistic Age. We can fairly claim that no other archaeologist of the 20th century so profoundly transformed our understanding of an ancient Greek sacred place.

He was joined in this effort by architect John Kurtich, in a successful collaboration that lasted some 30 years.

Although a person of few words, particularly later in life, Jim was one of great feelings. His loyalty to Phyllis Williams Lehmann taught me how to respect others and their ideas, even as you dismantle them. He was obliged to present new evidence that undermined her research in the sanctuary, and yet he did so in such a kind and gentlemanly manner that she remained his greatest advocate. I remember once when facing an architectural problem, she said, “Never mind, Jim will figure it out.” and then she turned to me with that piercing gaze and said, “You know, he’s a genius.”

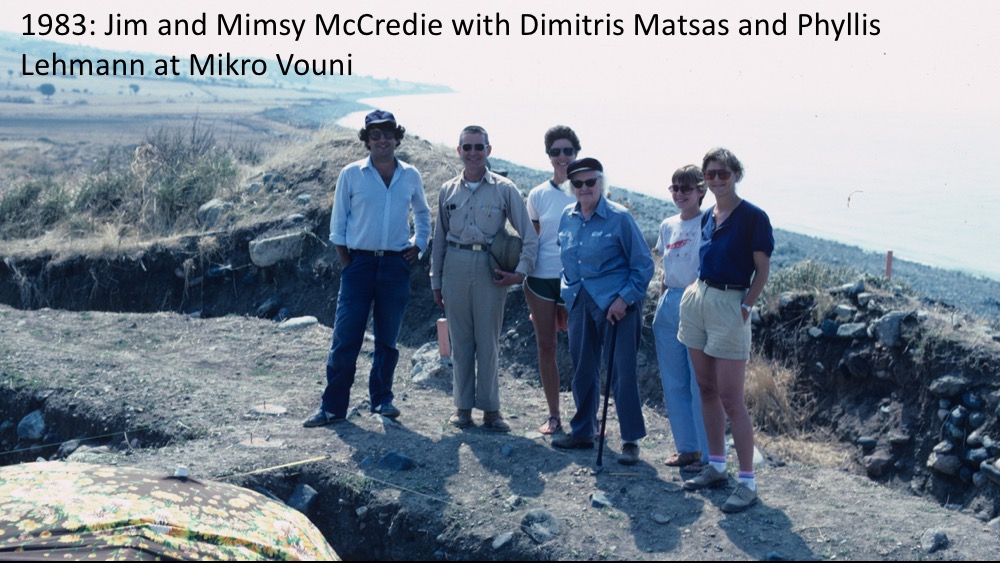

Jim was a splendid manager of the Sanctuary, working seamlessly with four Greek ephors over the course of his directorship. His longest collaboration was with Dimitris Matsas, who shares these words,

“We met for the first time on July 4th, 1980, in front of the entrance to the Museum of Palaeopolis, Samothrace, on the occasion of installing the commemorative plaque of Karl Lehmann on the exterior of the building. I saw him for the last time before his departure from Samothrace in August 2017. His last e-mail to me was on January 1, 2018, with wishes for the New Year and expressing the fear that “I have been to Greece for the last time, but Mimsy and Miles may come.” Since 1980 we’d met every summer on the island for 37 years, in my capacity as permanent representative of the Ministry to the work of the American School in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods.”

Dimitris continues, “I was involved with archaeological research outside the Sanctuary, but I also was responsible on the part of the Ephoreia for the site management, the first phase of which started when Jim was still director of the excavations. His contribution was valuable, both to the preparation of the plan and its implementation. Jim respected and he was very generous to colleagues, both Americans and Greeks, however lonely and remote sometimes he has been. He shared his knowledge of the monuments of the Sanctuary. Also, he assisted with his own money many times the work of the Ephoreia,...”

“...especially paying the workmen cleaning the Museum and preserving the Sanctuary.”

And he closes: “As archaeologists we are familiar with the ‘longue durée’ of history, supposing that we shall follow it also as human beings; but the loss of a relative, a close friend or colleague reminds us our human short-livedness. However, the life of James R. McCredie was full of successful historical work and as such will bring him the ‘longue durée’.”

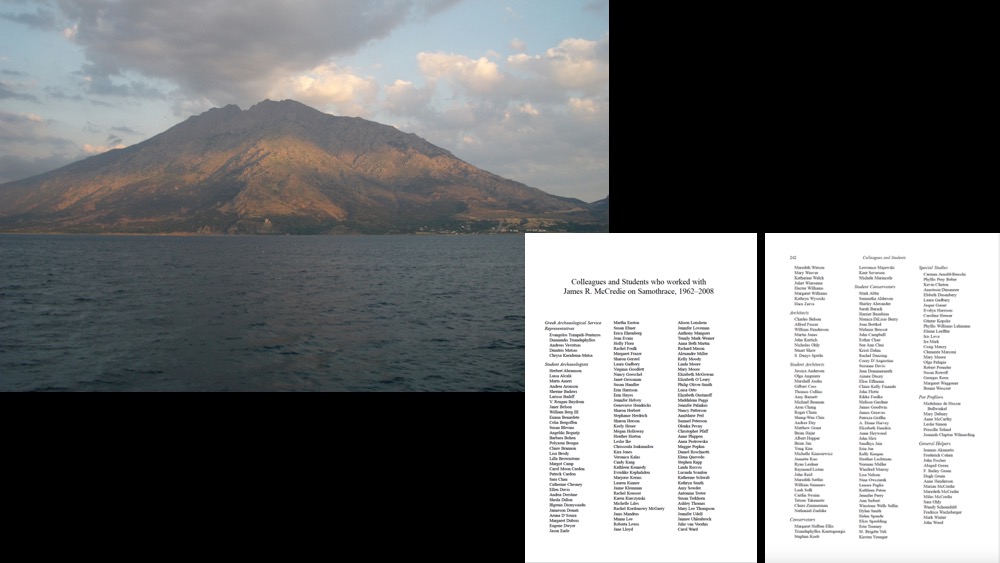

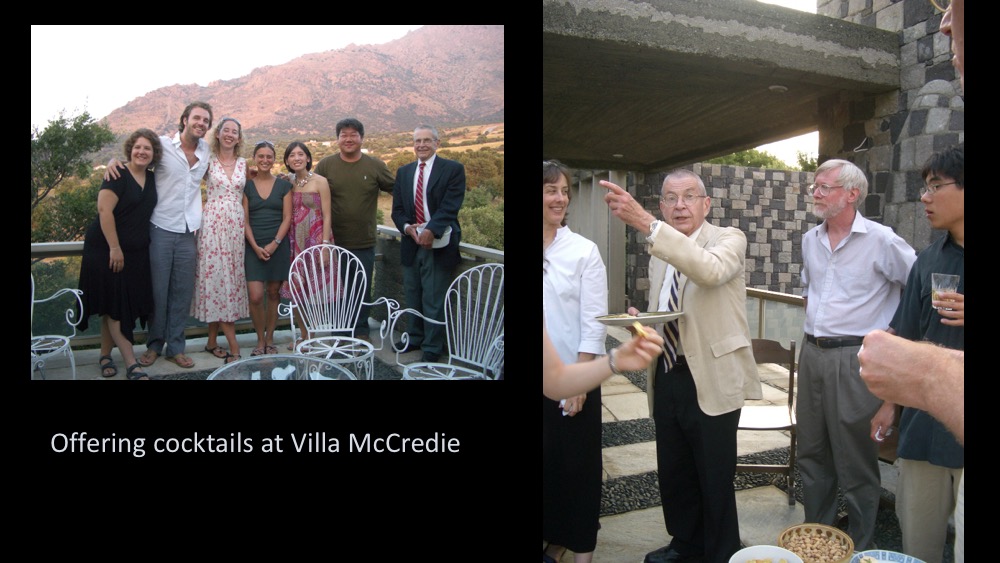

Jim’s relationship with the Samothracians themselves ran deep. He trusted and relied on the first Giorgi who built the Villa McCredie to look after it for many years, and when he passed, the second Giorgi took over. He was the most famous resident of the island and its much-revered honorary citizen.

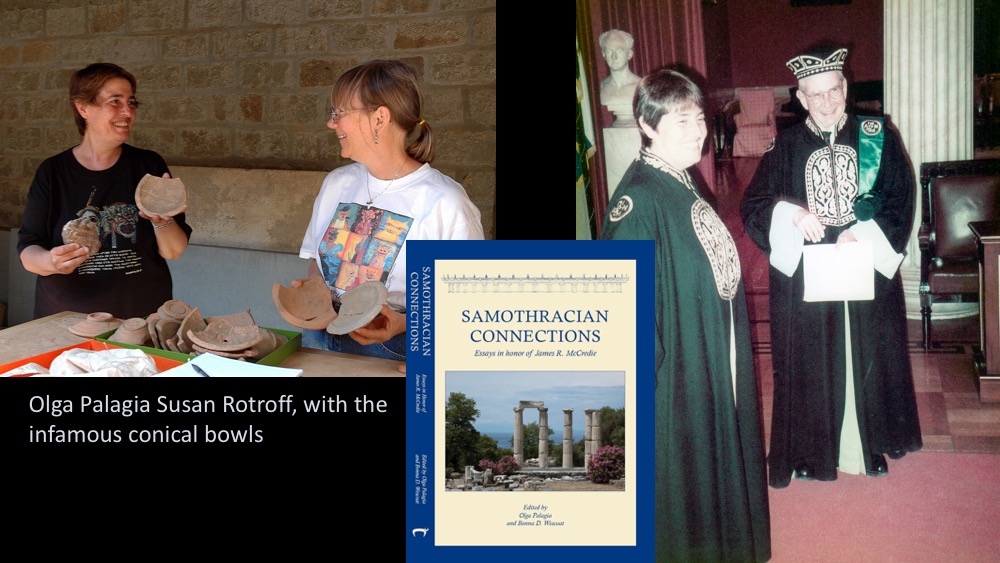

The island of Samothrace is not easy to get to, but Jim made it a Mecca for scholars interested in the Hellenistic world, several of whom you have heard from today. One such scholar was the world-renowned expert on Greek sculpture, Olga Palagia.

Olga Papagia shares this eulogy:

“I am grateful for the opportunity to be with you all in spirit and to pay tribute to a friend and mentor who inspired and encouraged me to study the sculpture of Samothrace. Over several visits to Samothrace I participated in the adventure of getting to know a little bit of this mysterious island and of its high priest, whose wry wit as well as his silences were a good match for the mood of the place. I will always remember his generosity and his encouragement; offering him an honorary degree from the University of Athens and collaborating on editing his Festschrift were small tokens of my debt to Jim McCredie, whose memory we all cherish.”

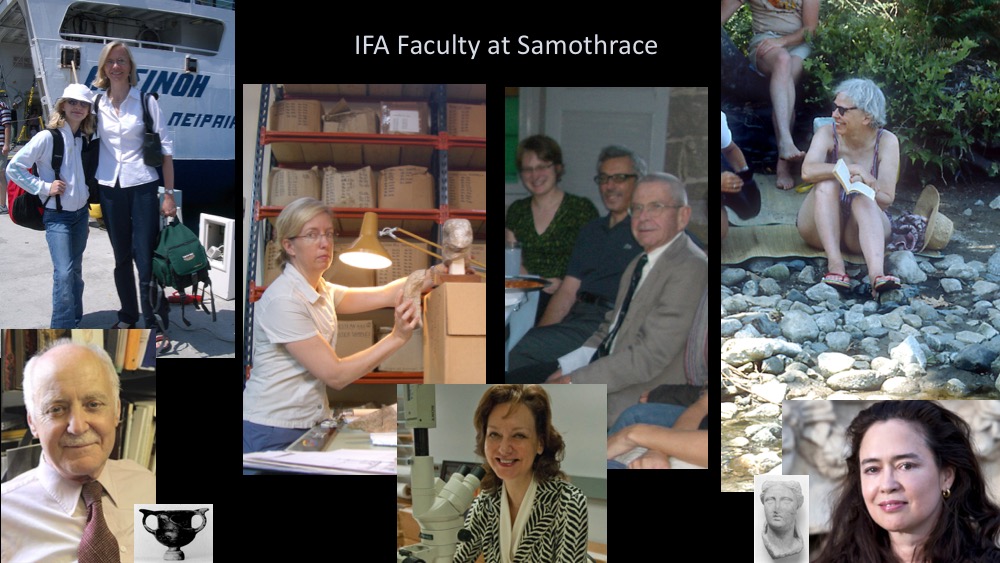

Jim McCredie also made the excavations a signature venture of the Institute of Fine Arts by including its faculty in many facets of the project: Guenter Kopke, Mariet Westermann, Michele Marincola, Peggy Ellis, Clemente Marconi, Evelyn Harrison, and Katherine Welch have all been involved in research and conservation.

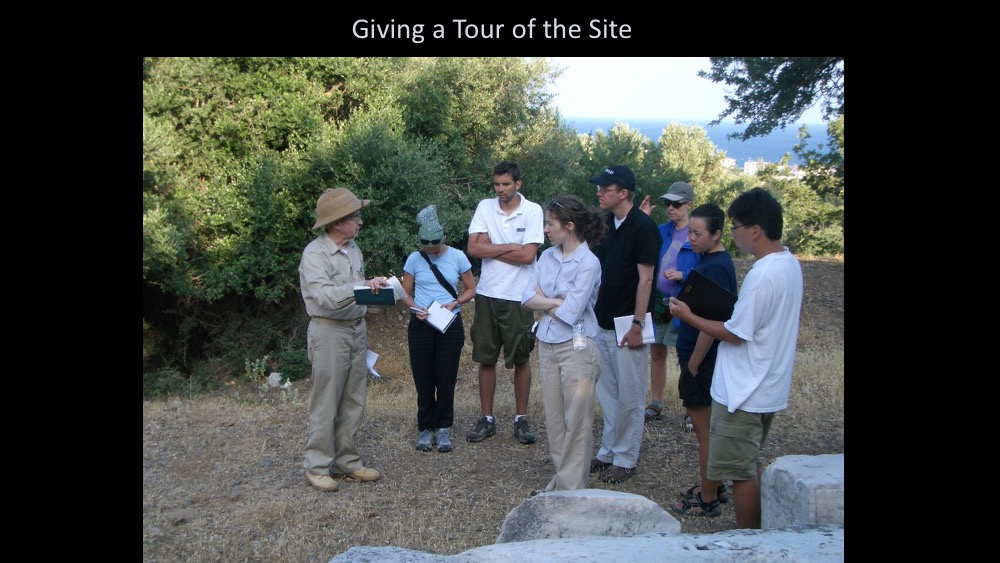

The remoteness of Samothrace was also no deterrent to the steady stream of students who came to work with Jim over the summers. Although his discoveries made Jim McCredie justly famous within the archaeological world, he was especially proud of the many students who trained under his leadership. He valued the expertise of specialists as well as the strength of young and “fresh eyes.” He encouraged students in all periods in the history of art, archaeology, and conservation to participate in the field research, expanding the impact of archaeological research and training across the disciplines. Some three generations of students and scholars learned and worked under his guidance and mentorship. Many of us owe their careers to his support and encouragement.

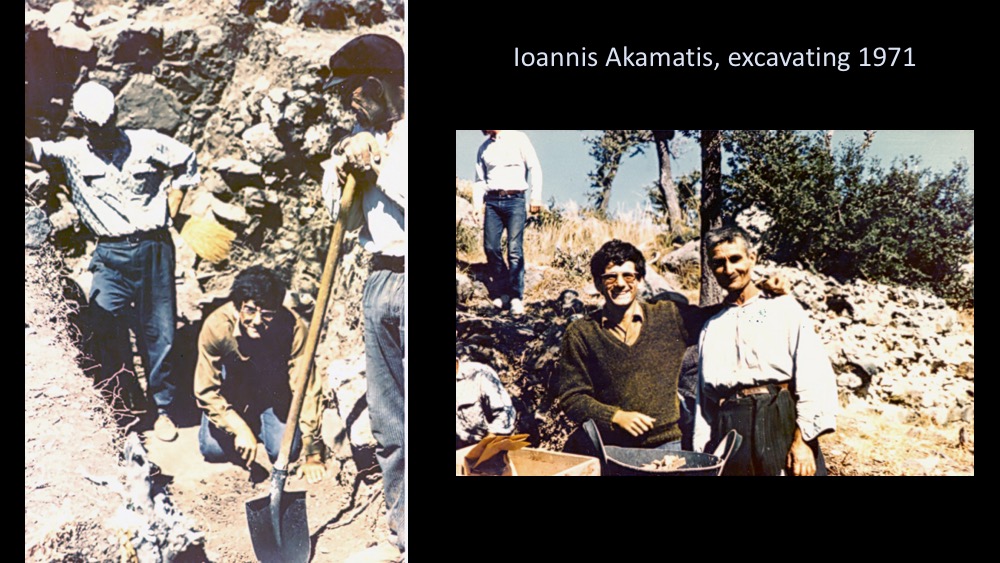

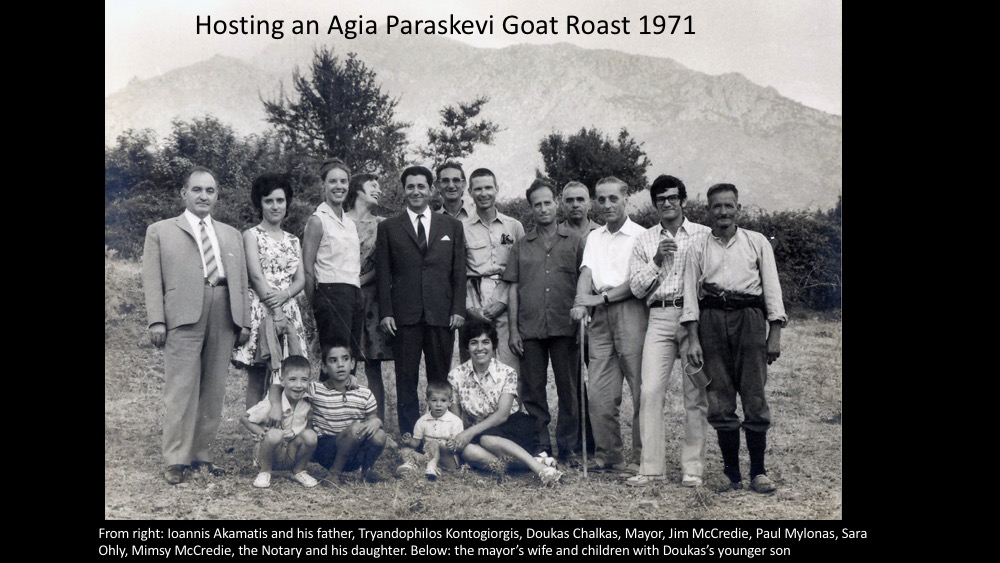

I am one, and another is Ioannis Akamatis, son of a Samothracian shepherd who became professor of archaeology at Aristotle University, Thessaloniki. He shares this tribute:

“I met Jim and Mimsy (Maria) upon their arrival at Palaeopolis Samothrace, in the early 60s. Jim sent me my first book on archaeology, which kindled my future interests. Soon, I got to know the person who directed the excavations at the Sanctuary of the Great Gods with missionary dedication, exhausting industry, and jovial good humor, all arising out of his absolute love for the task he was carrying out. Jim was a thoughtful and wonderful person, beyond any description. He was a mentor, providing unstinting support not only to me, but to anyone who wanted it. Samothrace, the ASCSA, the IFA, and the world as a whole won’t be the same without him.”

The list of those who wanted it is long indeed.

We Remember

There are signature moments, no matter what year one came to Samothrace, that we all cherish:

We basked in HIS PLAYFUL HUMOR, and his pleasure at student response.

There were the countless goat roasts, 4th of July celebrations, and Ouzo hours, as well as the very special and much coveted cocktails at Villa McCredie...

...and the constant of Jim and his orange Volkswagon Thing, Sylvester, waiting for us at the port.

CONCLUSION

World class archaeologist, colleague, mentor, and friend, we miss Jim dearly. But we find his presence in everything we do on the island: in the way we think, in the way we approach the site, in the way we treat each other. For the many years he gave to the island and to us, to the American School of Classical Studies and to the Institute of Fine Arts, we are all enormously grateful. For the many years his family graciously shared him with us, believed in the value of his gift, and accompanied him in the enterprise, we are grateful: to Mimsy, Miles, and Meredeth; Mark, Will, and Ellie. “Thank you” hardly suffices, but it suits Jim’s economy and gains force when said by hundreds. And so let me stand as one of those hundreds who give thanks for the life Jim McCredie shared with us.

Thank you.

Contact the Institute

Building Hours

Contact Information

If you wish to receive information on our upcoming events, please subscribe to our mailing list.