| Art History

| Art HistoryConservation

Archaeology

In Memoriam | James R. McCredie

A Celebration of the Life and Career

of James R. McCredie

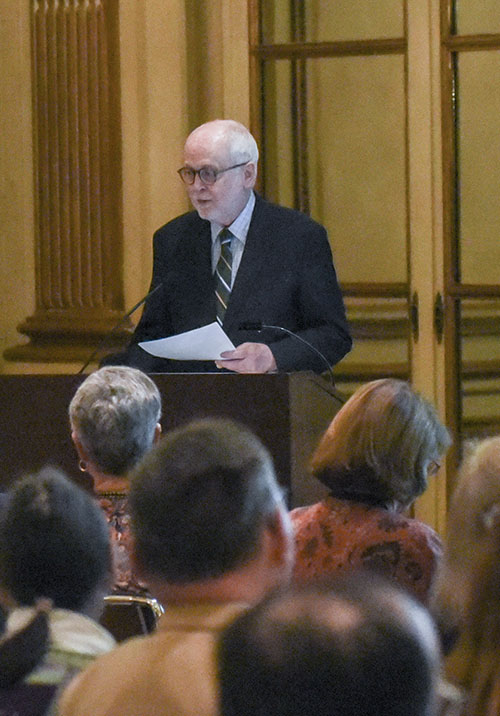

Robert Pounder

Professor of Classics Emeritus, Vassar College

In September of 1968 I arrived at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens as an associate student member. I had received an M.A. in classics from Brown, had completed the PhD preliminary exams, and was searching for an archaeological dissertation topic. My advisor, Alan Boegehold, thought that a year at the School, with its superior library, its unique program of site visits and seminars, its excellent excavation training program at Corinth, and the presence of eminent visiting scholars, would help me find the right subject and enhance my graduate education at the same time. Most of my fellow students that fall were just beginning graduate work, several of them having come straight from their undergraduate colleges, people such as Susan Rotroff and John Camp; also in the group were Mary Sturgeon, Steve Miller, Karen Vitelli, Hector Williams, Fred Cooper, Jon Mikalson and several others. I list these names because that 1968-69 class at the School produced a remarkable number of archaeologists, philologists and historians who continued in the field of ancient studies and became, indeed, some of its most productive teachers and scholars.

The director of the School that year, in his final term, was Henry Robinson, an accomplished archaeologist, teacher and administrator, who presided over the activities of the institution with a benign formality that built on the traditions established by his predecessor in the role, Jack Caskey, who in turn had learned from Carl Blegen and the long-retired Bert Hodge Hill, who had been named director in 1906 and served in that capacity for twenty years. In short, Robinson's tenure as director embodied traditions – some of them creaky and inflexible – harking back to the beginning of the 20th century. But a change was about to take place: we learned that autumn that a new director would be arriving in the spring, to settle in and confer with Mr Robinson before taking up the reins on July 1st. That new director was James Robert McCredie, and he came with his family, which included two young children, Miles and Meredeth, a governess, Mrs. Bowser, and of course his wife Marian Miles McCredie, known to all as Mimsy. Young children were a true novelty at the American School, and a sandbox and jungle jim and see-saw appeared for the first time ever at the bottom of the garden. These symbols of childhood play became metaphors for a transformation of the way the School was run.

The director of the School that year, in his final term, was Henry Robinson, an accomplished archaeologist, teacher and administrator, who presided over the activities of the institution with a benign formality that built on the traditions established by his predecessor in the role, Jack Caskey, who in turn had learned from Carl Blegen and the long-retired Bert Hodge Hill, who had been named director in 1906 and served in that capacity for twenty years. In short, Robinson's tenure as director embodied traditions – some of them creaky and inflexible – harking back to the beginning of the 20th century. But a change was about to take place: we learned that autumn that a new director would be arriving in the spring, to settle in and confer with Mr Robinson before taking up the reins on July 1st. That new director was James Robert McCredie, and he came with his family, which included two young children, Miles and Meredeth, a governess, Mrs. Bowser, and of course his wife Marian Miles McCredie, known to all as Mimsy. Young children were a true novelty at the American School, and a sandbox and jungle jim and see-saw appeared for the first time ever at the bottom of the garden. These symbols of childhood play became metaphors for a transformation of the way the School was run.

Most of the students in my year stayed on in Athens for a second year, some of them doing dissertation research, others working at Corinth or in the Agora. It soon became clear that a new era had begun. The McCredies opened their house to all, for teas and dinners and post-lecture receptions. Greek colleagues were always included, as were members of the other foreign schools. Young and old sat down to dinner together, Virginia Grace with a first-year student, Alison Frantz with a member of the Archaeological Service, Oscar Broneer with an Italian epigrapher. The food set a new standard, too, thanks to Jim McCredie's culinary skills; he taught the cook how to prepare everything from Thanksgiving turkeys to the best chocolate sauce you ever tasted.

Jim McCredie asked me to work with him as Secretary of the School, starting in 1970-71. I want to conclude these brief remarks by attempting to paint a portrait of the man and describe what it was like to assist him in the day-to-day running of the American School. No description of Jim McCredie could fail to note his brilliance as a scholar, a scholar who solved the mysteries of fortified military forts in Attica and created a painstaking reconstruction of the largest enclosed free space in a round building in the Greek world, the Rotunda of Arsinoe at Samothrace, among many other achievements. His rigorous Harvard education equipped him to oversee the education of others, to draw out the best in his students without an imperious dogmatism. This may explain the retention in graduate programs of so many of my first-year colleagues; his insights certainly helped me find my dissertation topic.

The core of Jim, I think, was a supreme self-confidence. But unlike many self-confident people, he was also modest and self-deprecating. But his assurance enabled him to confront opposing views without rancor and to guide the thinking of those who were forming their judgments. When a hard decision had to be made, he was not afraid to make it. His prose style was masterly. The letters and reports I drafted or wrote for him allowed him to tweak my own prose in ways that improved it forever. When he saw that your scholarly writing was going astray, he knew exactly how to correct it, and you, without the slightest offense, making you feel, in fact, as if the suggested changes were your idea. I am so grateful to him for that, as I am grateful also for his example of graciousness and generosity to everyone he encountered. He was perhaps the most polite person on earth. A slight shyness did not prevent him from being open and cordial. When I worked with him on Samothrace, he presided over the dig and those digging with precision and grace. He always knew what was happening in the trench before you did, but that didn't seem to bother or disappoint him, and it allowed you to learn from him easily.

Jim held every major position at the American School of Classical Studies – Chair of the Managing Committee, Director, President of the Board of Trustees, and others I've doubtless forgotten. He was arguably the most influential force in the School and in American archaeology in Greece of the 20th and early 21st centuries. His modesty and disdain for fuss and flattery sometimes made it hard for him to accept praise, but I think he knew how much he was admired by so many and was gratified by that.

One final thing. Jim McCredie hated it when people were late to meetings, or when meetings ran over the appointed timeframe. He also hated lectures that went on too long. Part of the purpose of a lecture was, for him, the distillation of an argument into as short a form as possible. Would that more of us were like him in that way. Well, Jim, if you're with us today, I hope you've noticed that I came in under schedule.

Contact the Institute

Building Hours

Contact Information

If you wish to receive information on our upcoming events, please subscribe to our mailing list.