As Above, So Below: Multiplicity and Migration in Estelio

By Lillian Beeson, Laura Sofía Hernández González, Barbie Kim, and Kaylee Moua Nok June 20, 2023

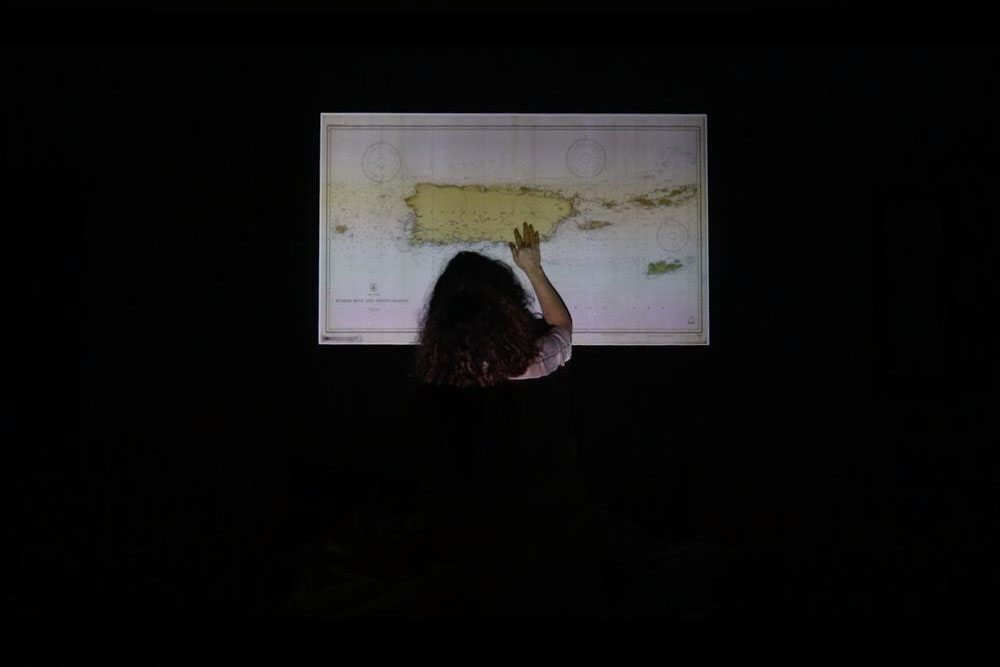

The ocean’s surface glistens and glitters; far below, sea life exists in dynamic ecosystems. As the tides push and pull, what lies below the surface, hidden in the depths of the ocean, is pushed ashore and brought into the light. The practice of artist Mónica Félix (b. 1984) likewise navigates the ebbing and flowing shores between the United States and Puerto Rico, the liminal space in which she and many others in migration find themselves caught. Félix has created a new vernacular in which astrological and oceanic aesthetics are used to investigate various exchanges: the complex relationships between Puerto Rico and the United States, colonizer and colonized subject, human and nature, and the stars and the sea—as above, so below. This expression, which has influenced occultism and several forms of spirituality today, speaks to the multiple layers of the universe and the relationship between the celestial world and the terrestrial world, providing vocabulary to define complex macrocosm-microcosm interactions. The earth and the cosmos retain their individual characteristics, but intersect as equals. Just as the tides move with the moon and the compass turns to the North Star, the artist’s embodied experiences of migration comply with the colonial institutions which define her condition.

The seven videos featured in this virtual exhibition emerge in response to her own lived experience. Each work is a microcosm within the larger macrocosm of Estelio. A sculptural seascape, from which the exhibition’s title is drawn, Estelio, 2023, groups marine objects collected from both coasts Félix inhabits: Puerto Rico and New York. Scallop shells, algae, salts, and other elements of underwater life are placed over a circular glass surface and arranged in a loose interpretation of the artist's astrological birth chart. For example, the lone larger scallop shell on the sculpture’s right indicates the artist’s moon placement in Taurus. It and the six other seashells reimagine the seven personal planets most commonly appearing in such charts—the Sun, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn—and organize the seven videos comprising the exhibition. Félix’s multiplicity of identities, experiences of migration and femininity, concern for the wellbeing of nature, and critique of colonialism in Puerto Rico and elsewhere all come together in the sculptural assemblage, which also orients the viewer through the artist’s personal videographic narrative.

Water permeates every facet of the artist’s work. In particular, Estelio’s assembled objects are evidentiary material, translating a story the ocean speaks. “The ocean is sick,” Félix observes. After the Spanish-American War and the United States’ invasion of Puerto Rico in 1898, the island’s waterscape became significantly polluted. The colonial forces perennially altered the local natural life, and Puerto Rico continues to suffer environmental crises as a result. Curators Iberia Pérez González and Natalia Viera Salgado warn that “the island’s streams and rivers are running dry, lakes are shrinking, and aquifers are being critically depleted.” Climate change, the mismanagement of water sources, and the increasingly capitalist economy in Puerto Rico threaten the availability of safe potable water. The presence of water in Felix’s art screams the colonial history of Puerto Rican identity. The sculptural Estelio opens a portal to the environmental tensions from coast-to-coast and presents the collected marine objects as a metaphor of the human body in migration.

Vaivén (Sway), 2019, explores how various personas can exist within a single individual, exacerbated by migration. Here, Félix grapples with the knowledge that Hurricane María is devastating Puerto Rico, where her family still resides. Yet despite her physical removal from the impact of the hurricane, she too is distressed by the storm. The camera serves as a mediator between Félix’s physical and mental states. The work begins with a pair of disembodied hands struggling to open a can of corned beef—a familiar scene to those who have endured hurricanes, and the meal her own family eats during such situations. The figure’s anonymity allows the viewer to envision an individual from their own household, making the shot personal. The video then cuts to Deborah Martorell, a Puerto Rican meteorologist, warning of the hurricane, and then to Félix’s own worried visage as she listens to the forecast. She pauses the video, unable to listen further without calling her mother—both to reassure her and to be reassured. Their call ends, and Félix is alone for the remainder of the video. Performing solo for the camera, now in Puerto Rico, the artist rustles bushes, rattles windows, and presents the intensity of the loud storm in all-encompassing darkness. The video abruptly cuts from the blackout and cacophony to Félix waking up, now once again in the stillness and material comforts of her New York apartment, emphasizing the disparity between her deep emotional connection to Puerto Rico and the barriers—of communication and proximity—that physical distance creates.

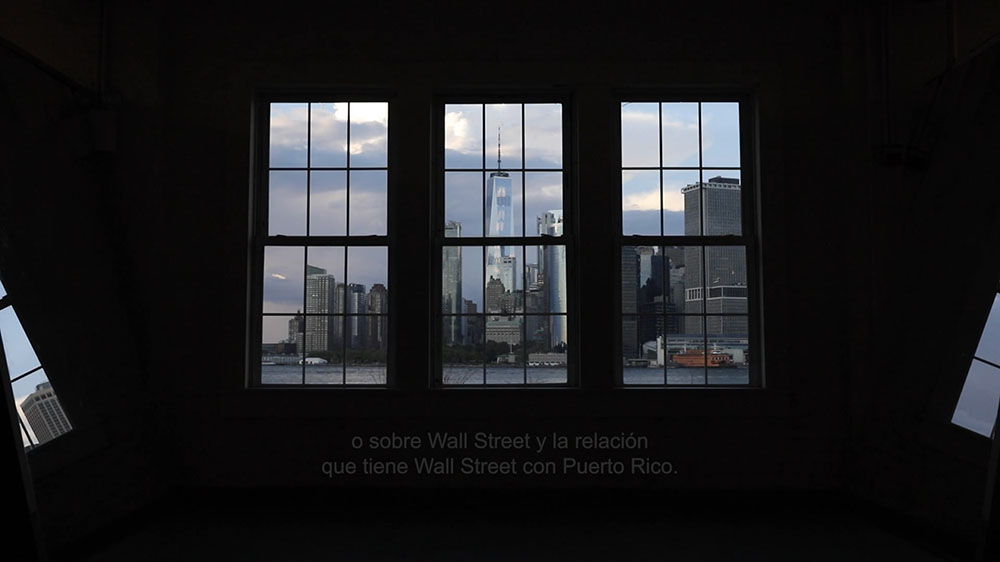

In Aves de rapiña (Vultures), 2022, the camera sits facing One World Trade Center for ten minutes. The static shot, framed by three windows in the artist’s studio on Governors Island, where she was in residence, captures Wall Street floating just above the water as ferries, yachts, and other boats occasionally drift across the scene. Just out of either side of the frame are two mirrors, the corners of which reflect the view. Accompanying the visuals are the voices of Puerto Rican people now living in New York, examining the relationship between Wall Street—not only a physical site, but also a symbol of the global banking industry—and Puerto Rico through a steady view of the financial district. Through the voices’ personal testimonies, Aves de rapiña, like Vaivén, explores the duality of existing both within and between two regions through an anticolonial lens. The speakers discuss how the United States’ political and economic exploitation of Puerto Rico has led to their displacement, and how moving from one region to the other creates inner conflict because of this troubling relationship.

Since its opening in 2014, One World Trade Center, along with other architectural and cultural additions to the city by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, have acted as beacons of downtown Manhattan—part of a purposeful revitalization of the area following the attacks of September 11, 2001. The tallest building of the World Trade Center complex, One WTC, is a monument to community building and healing that is just out of the camera’s reach. Félix juxtaposes the picturesque scene, with its connotations of the mythic American Dream, with the spoken testimonies of those exploited by the nation’s economic games. Félix’s video captions are in Spanish, and purposely not translated into English, prioritizing Puerto Rican audiences who already know the situation all too well.

During migration, reminiscing on what is left behind is almost inevitable—even more so when the destination country has an adverse connection to the birthplace. In the short video Salá (Salted), 2023, Félix looks back to Puerto Rico through interviews with four other women born and raised in Puerto Rico, and who, like her, have joined countless boricuas that have moved to New York. The women’s voices play over different clips of salt as it appears when observed under a microscope. Caught by fleeting camera movements, the mineral’s colors shift from black and white to hues of green. The women narrate the varying connotations of the word—and colloquial phrases using the word—sal (“salt” in Spanish). They identify exemplary meanings, but also refer to Puerto Rican cultural experiences and slang. Examples include “estar sala’o/salá” (“being salted”), a sign of bad luck, salt’s capacity to heal wounds and saltwater’s capacity to “season” bodies following a long day at the beach. At the end, Félix appears on camera and writes, with her fingers, the words “ME VOY” (“I'm leaving”) on the sand of the Ocean Park beach in Puerto Rico. Being “salted” emerges as a distinctly Puerto Rican quality that hardly dissipates in New York, and in this way connects with Vaivén and Aves de rapiña in its exploration of multifaceted identities wrought by migration, the role of language and communication—or lack thereof, as in Vaivén—and processes of translation both literal and metaphorical.

In the four remaining works that round out the show, the artist translates her own feminized experience through the camera, historically an apparatus for the male gaze and its hegemony in narrative cinema. In Querida (The Classic Aerobic Woman Part II), 2014, the camera is invited into a feminine ritual, a night out of dancing, set to classical music mixed with the voice of a female fitness instructor narrating aerobics instructions. Sharp red stiletto nails dance across the screen and sequined tops refract light. Within the haze, the women’s bodies begin to move with each other, becoming one connected group. They move organically and in slow motion, as if they were seaweed taken by the current. The vocalized instructions would seem to dictate their movements, but the bodies onscreen reject the authoritarian voice and move to their own beat, one that conforms neither to Western classical music nor to the American aerobic instruction. The camera, with its low, but straight-on angle, becomes a dancer as well—implicating the viewer into the seductive ritual and into the embrace of metaphorical sisterhood.

Sororal relations are also confronted in Alláfuera (or otherwise the United States), 2021, which reimagines Hans Christian Andersen’s 1837 story, The Little Mermaid, adapting it to Félix’s ongoing interests. Here, she uses wigs to act as the six sisters of the story in turn. The youngest sister, la Sirenita, takes the primary focus, for she is the one who undergoes change and suffering to gain an eternal soul. After la Sirenita leaves home, Félix shows her nude body—made human through the loss of tail and tongue—struggling to stay afloat in the water. This is juxtaposed by a graphic of the flight path from Puerto Rico to New York City. Such imagery evokes Félix’s personal journey of leaving la isla, where by her own account she is happiest, to pursue her artistic career in New York. In her adaptation, Félix eliminates the role of the male “prince” from the story and highlights la Sirenita’s sacrifices by visualizing the “pain” of anthropomorphic walking through a scene of broken glass on the beach. These and the scenes of the other sisters are shot in high resolution, directly contrasting with the blurred, heavily-tinted, and low frame rate found footage of swimming mermaids that imbue Félix’s version of the canonic story with ambiguity and mystery. This cinematic disparity formalizes and heightens the distinction between where la Sirenita came from and where she is going.

One of her most celebrated projects, Romance Tropical, 2013-2020, similarly challenged orthodox roles of femininity. The project is titled after a 1934 film of the same name, Romance Tropical, the first ever Puerto Rican sound movie, presumed to be lost after its sudden disappearance in the late 1930s. The film adheres to the structure of a “hero’s journey,” in which a man experiences both the successes and failures of love by manipulating and objectifying the women he seduces. During the span of seven years, Félix researched the film’s history, resulting in two works: Romance Tropical (Raquel and Ernestina), 2016, and Romance Tropical (RGB), 2020. The first is the story through the perspective of the film’s two stars, the actresses Raquel and Ernestina. In Félix’s feminist puertoriqueña translation, the artist herself plays both roles, first plunging the viewer into the sea, where two feminine bodies are caught in the waves’ strong undercurrent, grasping at each other’s arms in an attempt to find some safety. The poem “Danza Negra” by Luis Palés Matos—the renowned Puerto Rican credited as the writer of the 1934 film—is chanted as the imagery unfolds. The video concludes with an arm washed onto shore, its owner transported to a different state of being, reflecting the transformative experience the women might have felt as they were toyed with by their lover—unseen in Félix’s version.

After a copy of the 1934 film was rediscovered in the University of California, Los Angeles Film & Television Archive in 2017, the artist returned to the project. With newfound access to the original film, Romance Tropical (RGB) uses a digital camera to film a projection of the original at different shutter speeds. With this technique, Félix parsed out the red, blue, and green that fuse together as black and white in the digitized archival copy of the original celluloid reel. By doing so, she created a “colorized” version of the entirety of Romance Tropical. This version confronts the racist and sexist plot in the original film, as it prompts the viewer to think of the movie as an object that has traveled through time. Félix's colorized version reflects how present-day spectators might resent the original movie's plot, as opposed to 1930's audience when, as the artist states, the film was not deemed problematic. Additionally, the original film is inaccessible to most Puerto Ricans as it is owned by UCLA. By “reusing” the original film in her colorized work, Félix is simultaneously making the film accessible to more people. The artist also captioned a digital copy of the entire original film and uploaded it to her Vimeo, keeping with her advocacy for access.

Informed by feminism, anticolonial perspectives, and environmental consciousness, Félix’s practice mobilizes diverse media and her own body in dynamic interconnection with voices of others from her archipelago of origin and the colonial source material she often incorporates. By presenting Félix’s video works together for the first time, Estelio demonstrates the artist’s commitment to the specificities of Puerto Rican experiences of migration in the twenty-first century, though, like the ecosystem of marine objects visualized in the sculptural Estelio, the seven video works of this virtual exhibition travel across the past, present, and future—and often across oceans, touching different coasts.