Retrieval and Resonance: Rose Salane’s Art of Assembly

By Kaleha Kegode and Christina Shen

Rose Salane (b. 1992, New York, USA) meditates on the rich afterlives of people, places, and events through her collection of “dynamic sets.” Salane’s accumulations resonate with the notion of “souvenirs” which, as poet and critic Susan Stewart writes, are objects that circulate in the world and become “saturated with meanings that will never be fully revealed to us.” [1] Yet while Stewart emphasizes souvenirs as objects of nostalgic desire—narrated through longing and transformed into personal talismans—the artist surfaces the multifaceted, and often emphatically public histories embedded in her chosen objects. Rather than rendering her collected objects private or overindulging in sentimentality, Salane critically reanimates them, rescuing them from invisibility and obsolescence to foreground their relationship to the present.

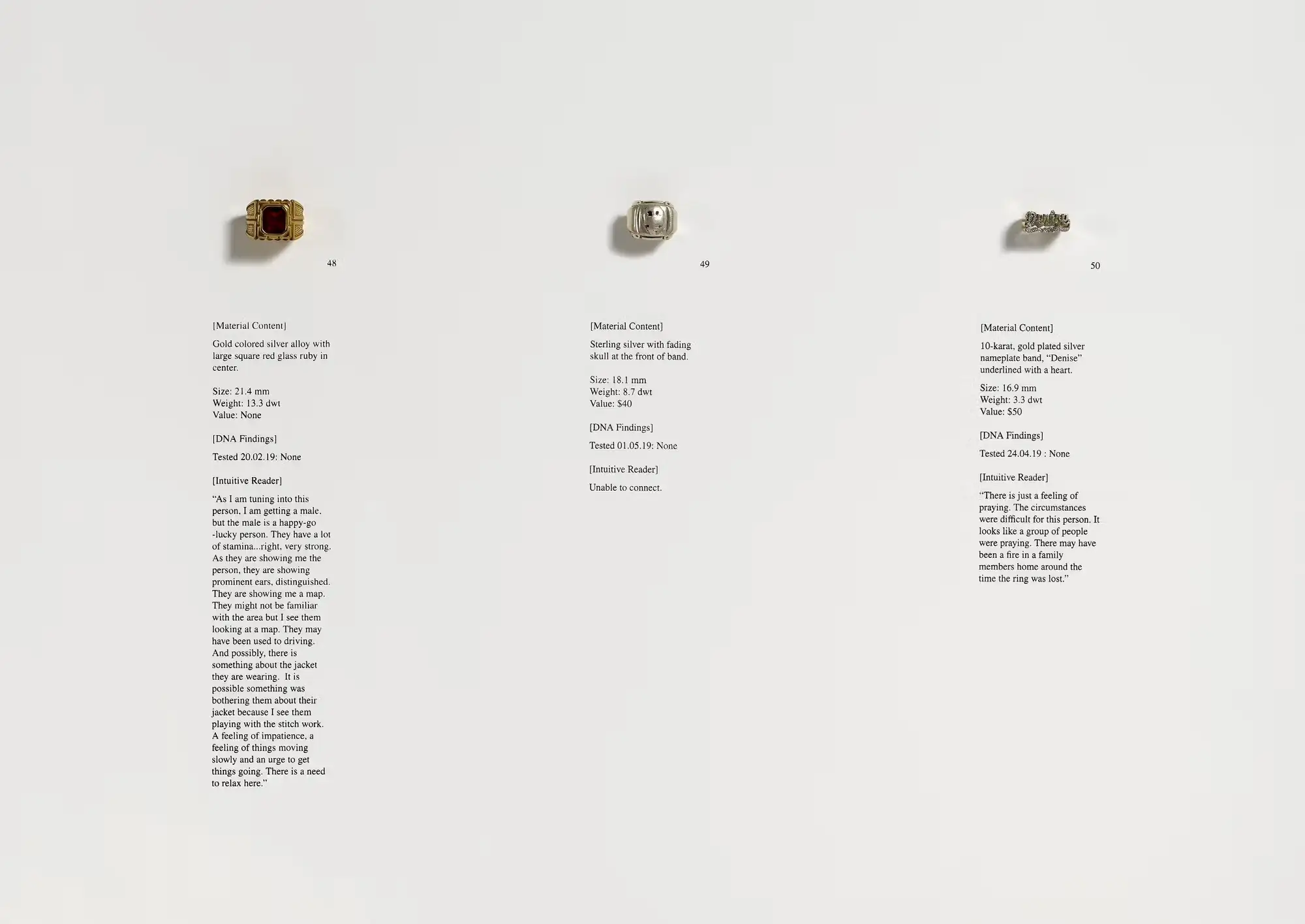

Salane’s past projects have been highly collaborative and worked across various disciplines outside of visual art. In Panorama 94, 2019, the artist documented a collection of lost rings found on the New York City subway (Fig. 1). She enlisted a jeweler, a biologist, and a psychic to recover material, DNA, and other latent personal information about the rings’ original owners. In Indigo237, 2018, Salane and her collaborator Deborah Rodi displayed a series of artifacts and texts formatted as news clippings from Windows on the World (Fig. 2). This restaurant was destroyed in the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center. In the wake of a historic tragedy, Salane and Rodi retrieved everyday ephemera to present the remains of memory.

Attention to what is left behind, exchanged, and accumulated in urban environments continues to propel Salane’s evolving practice. In Periphery in Red, Yellow, Blue, she expands upon these themes, finding collaborators in the Institute of Fine Arts’ scholarly community. Utilizing materials in public circulation and from the institution’s study collections, she juxtaposes distinctly industrial materials with the grandeur of the James B. Duke House, a Gilded Age mansion and former private residence that was completed in 1912 (Fig. 3). The exhibition weaves together complex histories of colonialism, industrialization, and exploitation through the lens of color.

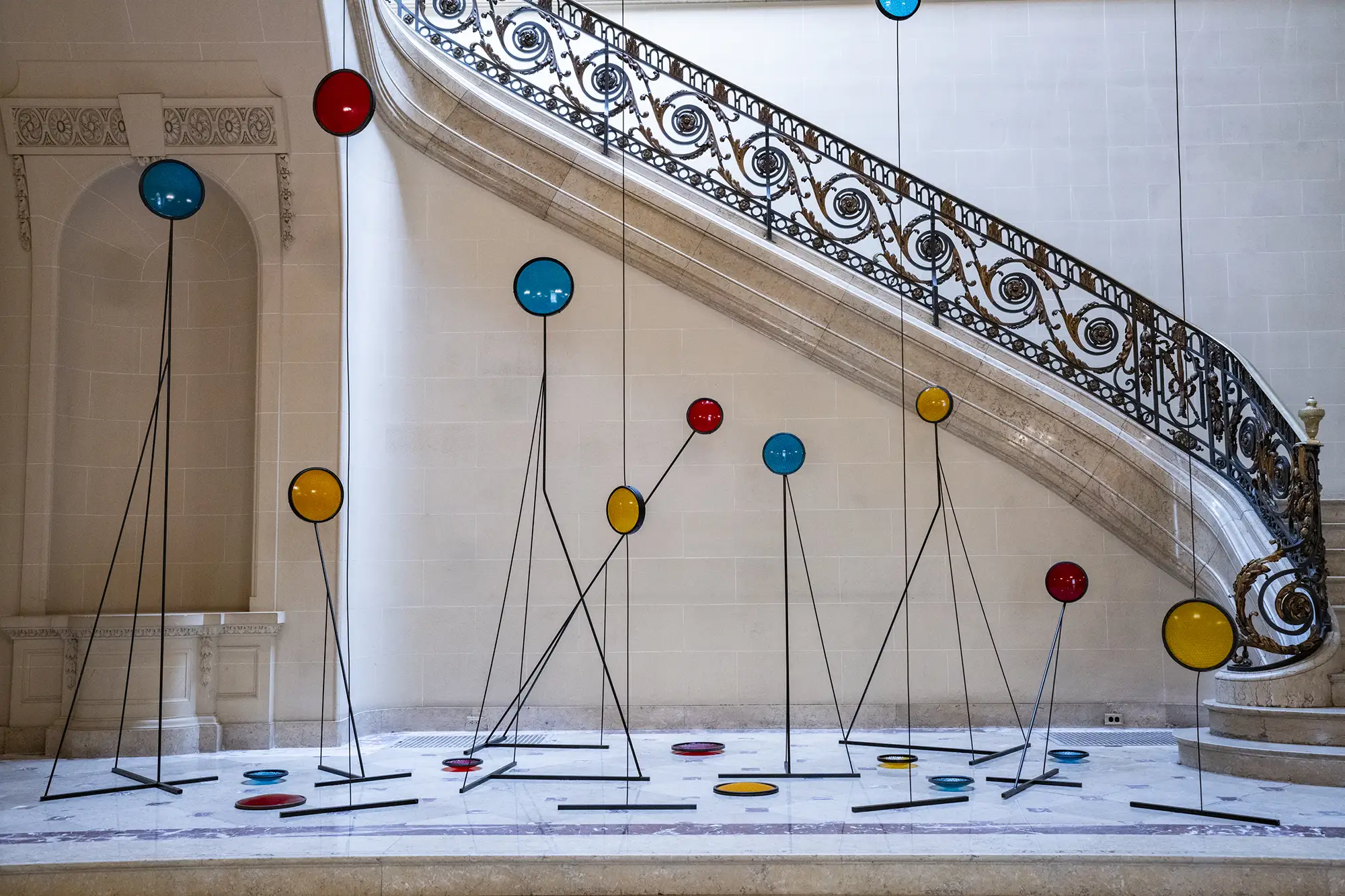

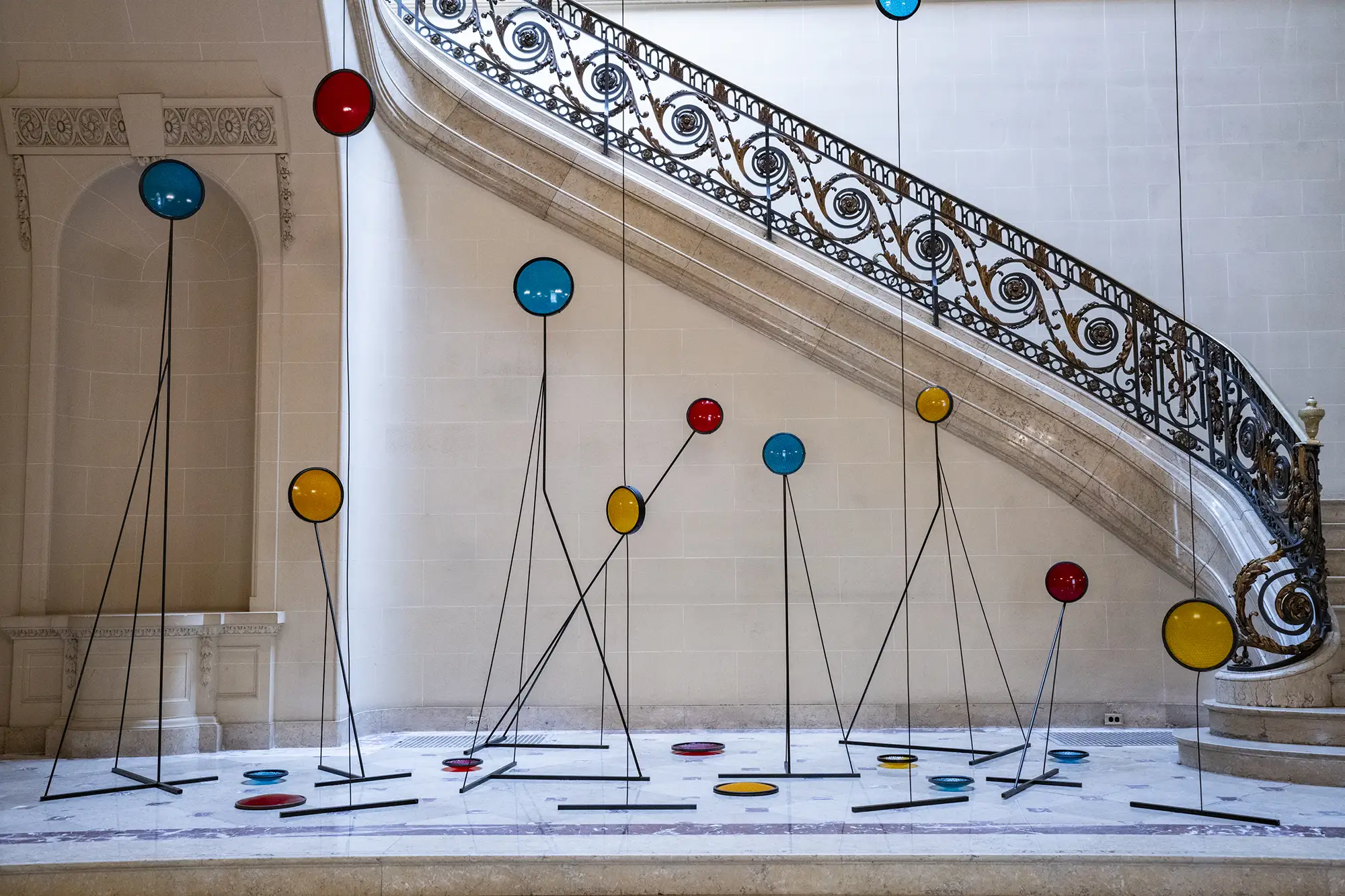

The exhibition’s centerpiece, Intersection; a grid in points (continued), 2025, brings together decommissioned traffic light lenses that Salane acquired from the NYC Department of Citywide Administrative Services at a municipal auction. The red, yellow, and blue glass lenses once organized the flow of traffic on the streets of New York City before LED lighting replaced incandescent bulbs in 2001. The artist places the constellation of lenses in the historic interior of the Duke House’s Marica Vilcek Great Hall, which both amplifies their status as outdated objects and summons the bustling intersections of colorful lights that glow and dim across New York City’s streets (Fig. 4). Fitted into steel armatures, several lenses are suspended in mid-air with draped cords, some are elevated by freestanding steel supports, while others rest directly on the floor of the Great Hall. Previously directing and restricting mobility through signs of “stop,” “wait,” and “go,” the dynamically positioned lenses convey the authority of objects and colors in enforcing a systematized process of spatial movement in the city. After the lenses’ retirement, they were subject to other bureaucratic processes, such as the municipal auction; as art objects, they are now presented in an instructional space with its own set of administrative delimitations. Salane navigates these official infrastructures to highlight how urban life and the capacity for movement are shaped by broader apparatuses of power, technology, and obsolescence.

Similar ideas about movement and material memory animate Salane’s engagement with the IFA Conservation Center’s Forbes Pigment collection (Fig. 5). The collection’s originator, Edward Waldo Forbes, was the former director of the Fogg Museum at Harvard University. Forbes saw value in collecting pigment specimens from all over the globe to advance art historical and conservation scholarship. Both institutions no longer utilize the pigments for scientific analysis; instead, they are preserved as a material reminder of social histories and as pedagogical tools. These pigments were circulated in colonial trade, used in significant cultural practices, and evince changing technologies.

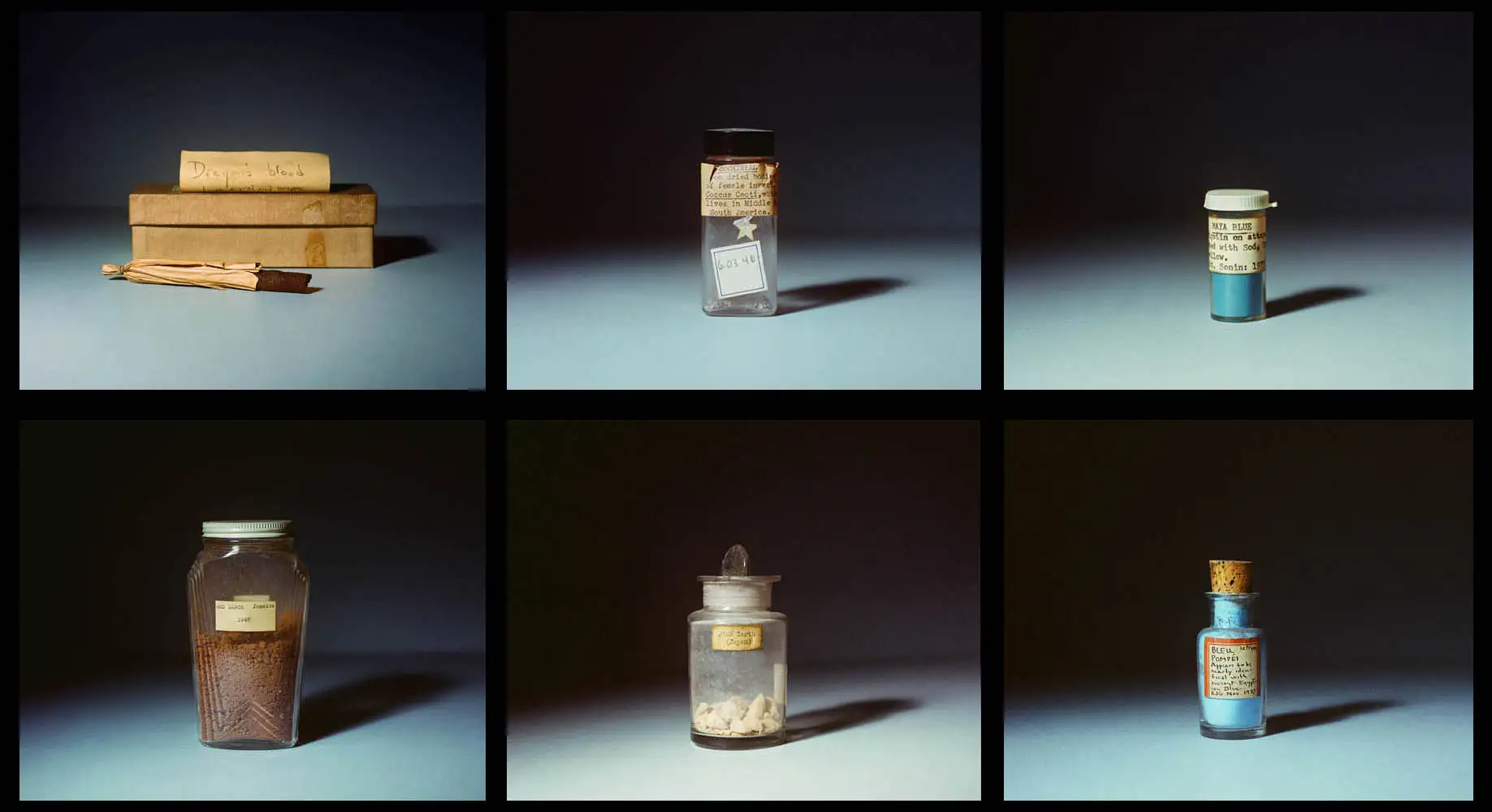

Pigments are insoluble materials that are commonly combined with binders to produce paint media. They frequently come from the earth but can also be produced synthetically. [2] As Caroline Fowler and Ittai Weinryb describe, pigments contain histories of extraction and power, two elements that are “central to the concept and formation of collections since the sixteenth century.”[3] Salane’s research in the Forbes Pigment collection resulted in two photographic assemblages, each grouping three pigments in an L-shaped arrangement. The individual pigments are photographed in a studio setting; their isolation and decontextualization as objects of examination is complemented by dramatic lighting. Each assemblage suggests a missing fourth piece of a grid, prompting viewers to consider the voids and historical interstices regarding the pigments’ extraction, production, and distribution. Through this work, Salane pursues questions such as: What can be preserved over an extended period of time? How do accumulations of discontinued objects leave behind historical remnants? What remains absent and why?

Despite the myriad questions that remain about the pigments, scholars have done intensive research to uncover their medicinal uses, spiritual meanings, and technological advancements necessary for their extraction and production. The first pigment print, Dragon’s Blood, Cochineal, Maya Blue, 2025, reflects metaphysical connections across spatiotemporal boundaries (Fig. 6). Imbued with potent cosmological forces, these pigments embody the threshold between the natural and spiritual realms. For example, Maya Blue was predominantly used during Mesoamerica’s Classic and Postclassic periods in the Northern Yucatan to the Guatemalan highlands and Central Mexico. Typically used to decorate pottery, statues, and wall paintings, the pigment’s importance derives from its cosmological significance. Maya Blue’s composition of indigo dye from the plant Indigofera Suffruticosa and palygorskite, a clay mineral, aids in its representation as the conjunction of the natural and the underworld.[4] To source the clay palygorskite, the Maya would excavate its limited deposits, which were accessible via mines within cenotes.[5] In Maya cosmology, these subterranean sites represent gateways from the land of the living to that of the dead. [6]Dragon’s Blood was the alchemist's pigment, deeply intertwined in mythology and highly favored in the Medieval Era in Europe. It was believed to have been acquired from the bloody residue of fights between dragons and elephants. Naturally derived from the Daemonorops plant genus and the fruits of the Dracaena rattan palm, Dragon’s Blood has been prized both for its medicinal properties and color richness.[7] The second print, Red Earth: Jamaica, Pink Earth: Japan, Pompeii Blue, 2025 represents some of the oldest pigments on the planet, connecting cultures across both time and space (Fig. 7). Red Earth has been used since Paleolithic times as a medium for cave wall drawings, while Pompeii Blue was produced to resemble Egyptian Blue, one of the first synthetic pigments ever created to adorn the walls of Ancient temples and tombs. [8]

Figure 7. Red Earth: Jamaica, Pink Earth: Japan, Pompeii Blue, 2025, Three inkjet prints in walnut frame, 42” L x 34” H x 1.5” D.

Strategically placed in the Lecture Hall, the pigments’ juxtaposition against the gilded and chandeliered room encourages students and audiences to remember these materials as important modalities of art historical inquiry. The pigments reflect moments of everyday life from their respective times, evident in the layers of information harbored in their hues, names, and the vessels in which they were collected. In the IFA Forbes Pigment Collection, Maya Blue is housed in an old pill container; Cochineal is marked with a mysterious star sticker; Red Earth: Jamaica is stored in a large glass jar; Dragon’s Blood is wrapped delicately in paper; Pompeii Blue and Pink Earth came into the collection in glass apothecary jars, the standard for conservators at the time. [9]

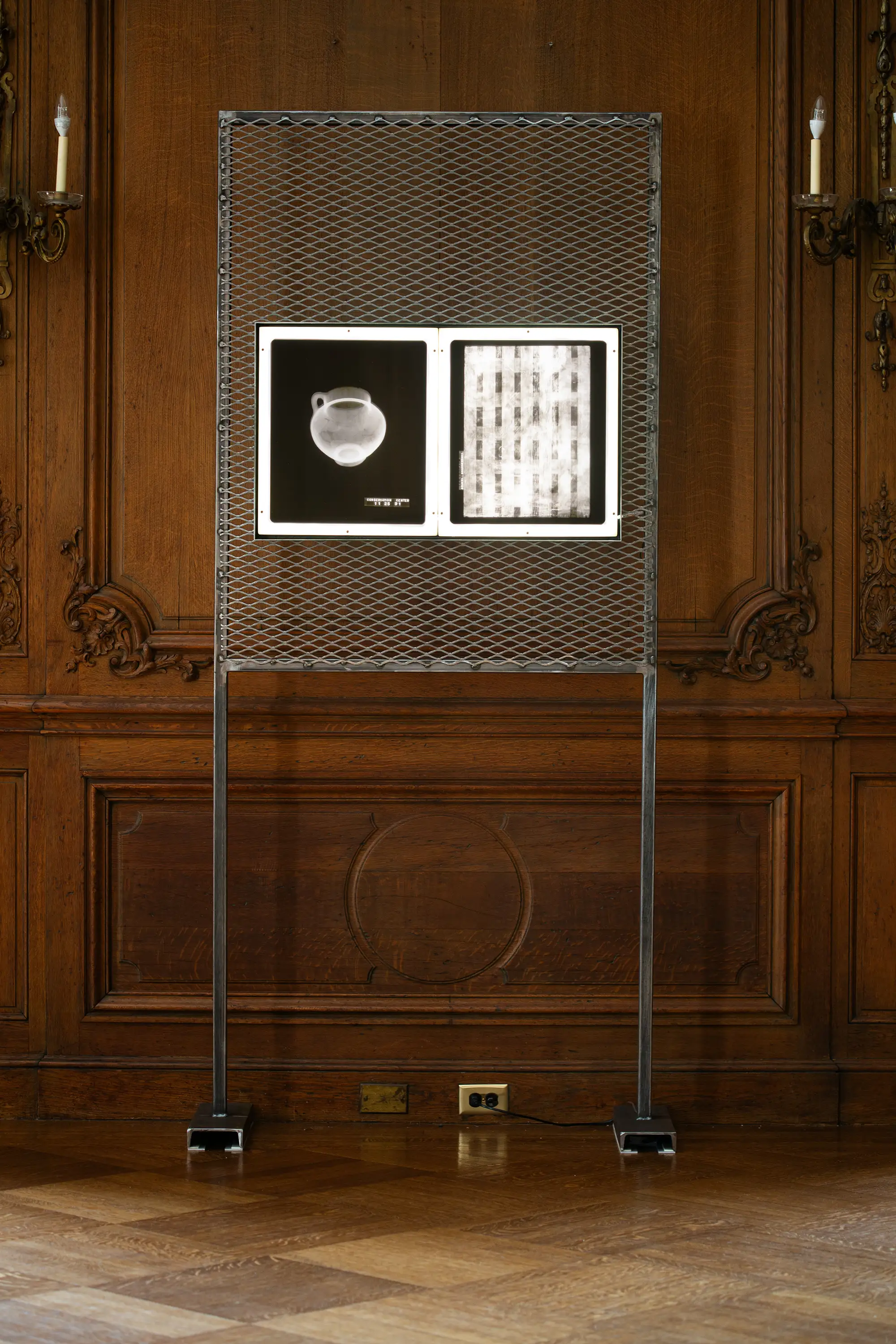

Salane presents two additional works on steel armatures in the former residence library, now called the Loeb Room. The space now displays books by alumni and faculty of the Institute of Fine Arts, continuing its pedagogical significance. Salane contributes to this ongoing conversation with Persian Bowl with Rubens’ Adoration, 2025, a work containing UV prints of an X-ray scan of a Persian Bowl and the Adoration of the Magi by Peter Paul Rubens, 1609. Both are mounted on and illuminated by outmoded light boxes previously used by Institute students and faculty to study slides. The X-rays remind us that art objects’ interiors, not only their surfaces, reveal much about their construction and meaning Fig. 8).

Across the room is Salane’s Conservation Reports, 2025, a silkscreen print that superimposes an array of conservation notes spanning a twenty-five-year period (Fig. 9). Hung on a cross-hatched steel support, the whiteboard contains typewritten texts describing the chemical breakdown of works of art and the physical properties of their component parts: “natural ultramarine,” “presence of CaCO3,” “isotropic, amorphous.” Others present more descriptive language—“Virgin stands on the stones opening her arms”—or demonstrate speculative analysis—“This painting may simply refer to the joyous life shared by Orpheus and Eurydice…” and “Leonardo? Alleged.” Next to these notes are ones handwritten by different people in a variety of styles and pens. A set of notes neatly written in red abounds with words that are struck through, revealing processes of editing.

These assembled texts underscore the many ways of producing knowledge about an object, be it through subjective description, material examination, or chemical analysis. Identifiable distinctions between typewriter and computer keyboard texts also suggest how technological advancements enable new methods of documentation. This work resurfaces voices from the Institute’s past, prodding viewers to question what is documented and lost as information is transferred over time.

Salane’s accumulated objects in Periphery in Red, Yellow, Blue trace desires and lost histories, but her artistic project is not nostalgia driven. This makes her work distinct from what Stewart views as the emotional and even fetishistic desire of souvenir collectors, who are compelled by the metonymic and partial qualities of the objects they gather. Salane’s self-reflexive work acknowledges its non-neutral mediation of objects and information, deliberately recontextualizing them to highlight incomplete historical records and obsolete technologies. These, her work shows, also expose broader systems of organization—whether in traffic control, pigment collection, or conservation practices—and systems of value, whether institutional, material, or technological.