“This meeting is being recorded.”

Not to be conspiratorial, but we are being monitored. As we walk through the streets, browse stores, enter buildings, and travel, cameras follow our movements. But more pernicious than merely being watched is the recent ability of security measures to monitor and interpret this footage. Using facial recognition technology, cameras can know who they are watching and interpret human activities and emotions without human aid. Undoubtedly, this can serve positive purposes in some situations, but the cost is high.

Massive quantities of data can be purchased and used for governmental and commercial purposes. With the expansion of government surveillance capacities, data collection has developed from FBI agents sitting outside suspects’ homes in unmarked cars to an indiscriminate international data collection effort first exposed by Edward Snowden in 2013. Since then, the advent of facial recognition software has provided an even more invasive method of surveillance that replaces human biases with algorithmic ones that do not always differ from those of their makers, who are predominantly white and male. Commercially, companies can use data to exploit vulnerabilities and micro-target ads to maximize consumer spending. Agreeing to terms and conditions on apps that deliver such content can ultimately mean signing away any semblance of privacy.

Artists working in reaction to this surveillance are researchers and activists as much as they are creators. Their work interrogates the mechanics of surveillance and the systems used to monitor and identify individuals. These “watchers of the watchmen” respond to the near-constant surveillance humans are subjected to wherever they may go. Eschewing traditional media like drawing and painting, these artists utilize photos, videos, and algorithms in creating their work, using the language of security against itself. This essay examines the works of several artists including Avital Meshi, the focus of the Great Hall Exhibition, and interrogates the media they use, their understanding of methods of surveillance, and their efforts to expose systematic biases.

The genre of surveillance art predates the internet. Andy Warhol is often credited for launching the genre with his film Outer and Inner Space (1966); it shows actress Edie Sedgwick interacting with previously recorded footage of herself. Warhol films her as she watches a recording of herself, creating a scenario that blurs the boundary between subject and viewer.

Artists such as Bruce Nauman made surveillance art that involved spectator participation, thereby blurring the boundary between video and performance. Nauman’s Live-Taped Video Corridor (1970) turned viewers into the viewed. A camera placed above the entrance captured the filmed likeness of individuals who entered the makeshift corridor as they proceeded toward two monitors in the distance. The top monitor presented the participant’s image in real time, seen from behind, as it grew smaller and seemed to retreat, even as the participant approached the monitor’s vanishing point; the other monitor featured a prerecorded video of the same empty corridor. These screens and the “security footage” they captured were crucial elements in Nauman’s corridor works, underscoring a chief concern of 20th-century surveillance artists.

Julia Scher takes screens as a primary subject in her works as well. For example, Mothers Under Surveillance (1993) intercuts images of the viewers with pre-recorded footage of elderly women in a recreational center, revealing that watchers can be simultaneously watched.

While these works promote awareness of the camera, they focus on footage and its display and not on the method of surveillance itself. As technology evolves and cameras decrease in size and grow in ubiquity (note how many cameras and recording devices are embedded in the device you’re reading this on), numerous contemporary artists turn the camera around to call attention to modes of surveillance. They often employ photography that documents surveillance mechanisms instead of what is being surveilled. For example, Jim Lo Scalzo’s Welcome to Watchington series (2013-14) exposes cameras, guards, and other detecting agents, placed by various private and governmental entities, throughout the nation’s capital.

Jakub Geltner installs groups of cameras and satellites in various locations, organizing them to resemble flocking birds or beds of mussels. In Nest 05 (2015), a group of surveillance cameras perches on seaside rocks. Pointed in different directions, their artificiality is undeniable, yet they resemble curious seagulls as they watch beachgoers and swimmers. They may also obliquely reference the Birds Aren’t Real movement, which advances the belief that the government has replaced all living birds with “Bird-Drone surveillance” agents.

Trevor Paglen is particularly notable in the field of contemporary surveillance art. Paglen engages in counter-surveillance efforts, documenting the United States’ infrastructure of surveillance. In his series Limited Telephotography (2007-12), for example, Paglen uses a long-range telescope to photograph government sites prohibited to civilians and unviewable with the naked eye. For Undersea Cables (2015-16), Paglen learned how to scuba dive to photograph underwater internet cables that play a crucial role in communications and surveillance.

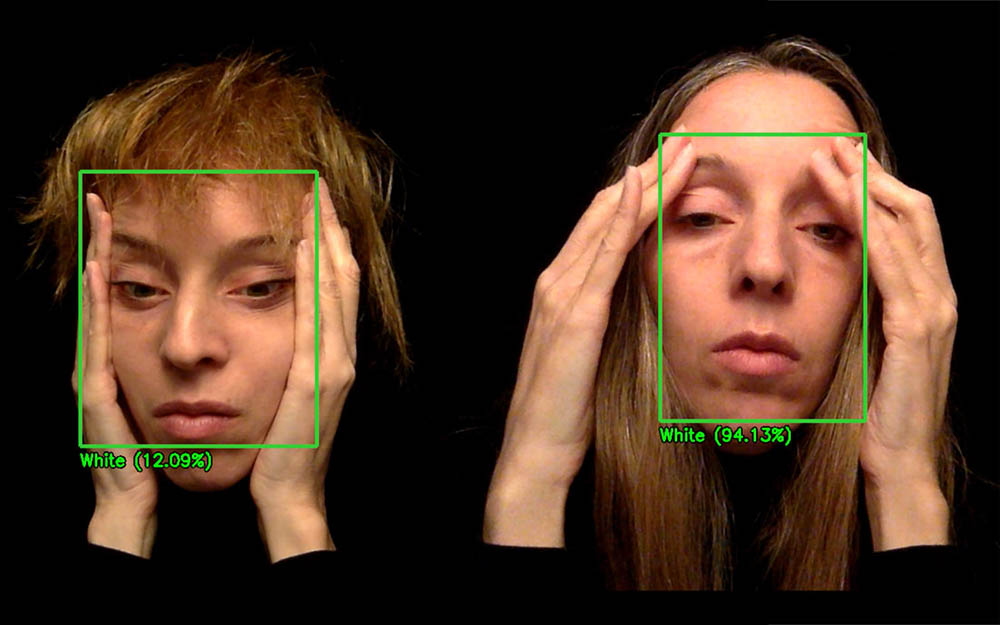

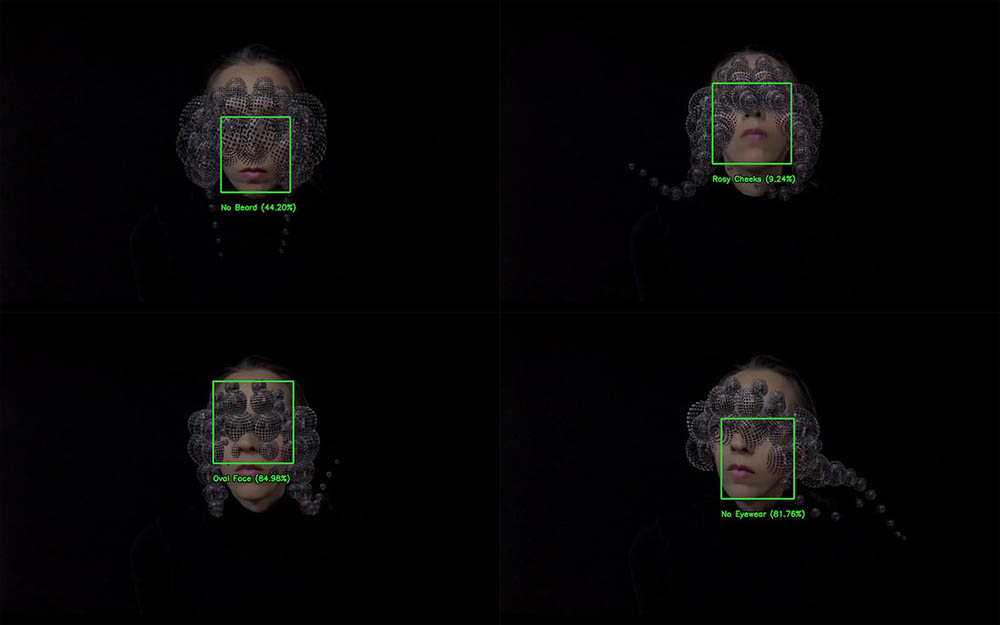

Similarly, Meshi’s work exposes processes not meant to be seen. In the case of Techno-Schizo and Deconstructing Whiteness (both from 2020), she reveals the bias of an algorithm that classifies her. Indeed, the datasets used to train AI facial recognition systems created a system where the highest accuracy rate is obtained when analyzing the faces of white males, with the greatest error rate for Black women. Meshi’s Techno-Schizo highlights just how faulty algorithms can be, as a machine reads her face and features with varying accuracy. The AI Human Training Center (2020) allows participants to understand how they’re read by an off-the-shelf algorithm in real-time; it allows them to confront how their faces can be misconstrued but also how they can be used to actively mislead facial recognition systems.

Meshi’s works address a growing concern as functions of daily life more heavily rely on machine decisions. Decisions that affect our lives, such as the cost of a product online, insurance, mortgages rates, risk assessments, and hiring processes are increasingly being entrusted to algorithms. As gender, age, and racial bias has been spotted in various algorithms–from platforms such as Google, Amazon, and Youtube, to the justice system–their accuracy has been contested.

The algorithm’s accuracy is a central aspect of Meshi’s works shown in this exhibition as well as in her other works such as Snapped (2021), Deconstructing whiteness (202), and Face it! (2019). All these works explicitly show a label and a percentage that states the “level of confidence” that the algorithm has–for example, in the left image of Deconstructing Whiteness, the algorithm is 12.09% sure Meshi is white, while that confidence increases to 94.13% in the image of the right. During her performances, Meshi playfully reacts to the level of confidence and engages in a dialogue with the algorithm by altering her expressions and posture. In doing so, Meshi pokes holes in the algorithms and emphasizes how problematic they can be.

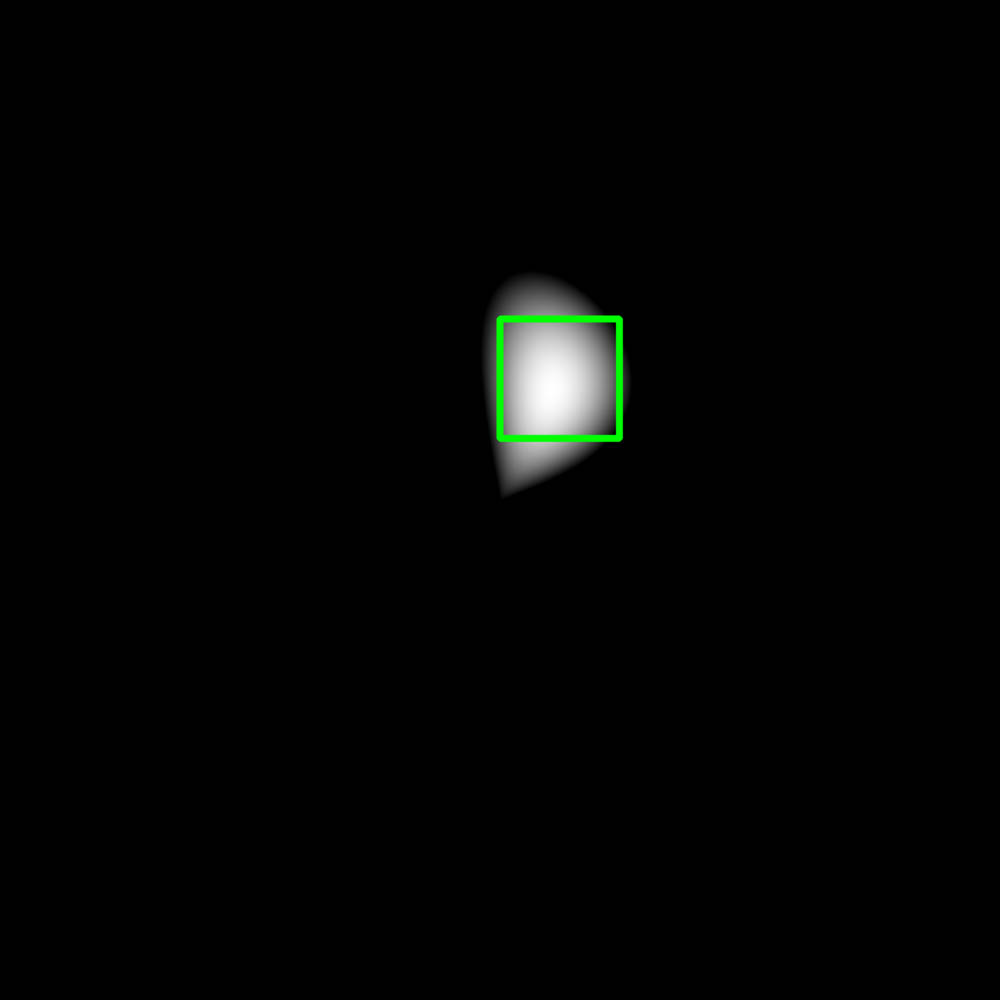

Similarly, in How do you see me? (2020) Heather Dewey-Hagborg creates portraits that the algorithm recognizes as her face. To comprehend how the algorithms work–widely understood as black boxes for their mysterious mechanisms–Dewey-Hagborg generated a series of images that “mutated” and propagated while still being recognizable as being a face. What it is recognized as a face, however, is in fact an abstract black and white gradient.

The Photographers’ Gallery, How Do You See Me? An Interview with Heather Dewey-Hagborg, 2019.

How do you see me? contrasts directly with the research and artwork of the “poet of code,” Joy Buolamwini; she launched her work precisely because her face was not recognized by an algorithm. This led to her advocacy on behalf of the “excoded” (those harmed by algorithmic biases).

“Advocacy – Poet of Code,” accessed March 13, 2022.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer titled an interactive project Level of Confidence (2015); this facial-recognition system compares the faces of the visitors with those of the disappeared students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College in Mexico. Debuted six months after 43 students were kidnapped, the project matches audience members with one of the missing students’ photographs and provides – similarly to Meshi’s work–a percentage of the level of confidence of that match. Lozano-Hemmer makes a point of using algorithms typically employed by the military and police (to look for potential criminals) to search for the victims of a massacre that, he states, involved the government, police forces, and drug cartels.

“Rafael Lozano-Hemmer - Level of Confidence,” accessed March 13, 2022

In subtle and poetic ways, the works by these artists highlight what activists have emphatically affirmed—that algorithms should not be blindly trusted. Not meant to be neutral or fair, they can only answer a question based on the data they have. Humans create algorithms with data that is socially constructed. As Meredith Broussard observes, “they are machines that result from millions of small, intentional design decisions made by people who work in specific organizational contexts.”

Meredith Broussard, Artificial Unintelligence: How Computers Misunderstand the World, MIT Press Ser (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2018)

Although accuracy remains a key aspect to consider, it is just a part of the problem. As Buolamwini notes, “accuracy draws attention, but we can’t forget about abuse. Even if I’m perfectly classified, that just enables surveillance.”

Joy Buolamwini in Shalini Kantayya, Coded Bias, Documentary, 2020.

Indeed, enabling surveillance is a chief concern of artists working in “surveillance performance,” a term Elise Morrison defines as a type of performance in which artists use surveillance technology as a central part of their production, design, content, aesthetics, and/or reception. These artists employ such technology as a way “to make visible - thus available for security and revision - the risks posed by surveillance technologies in social and political spheres.”

Elise Morrison, Discipline and Desire: Surveillance Technologies in Performance, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2016, 5.

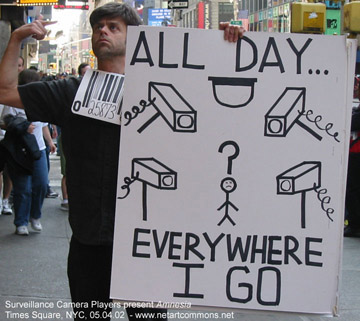

One such early artist-activist group, the Surveillance Camera Players (SCP), formed in New York City in 1996 in opposition to the police installing unmarked surveillance cameras in public spaces. By performing adapted plays in front of surveillance cameras, such as Amnesia (2002) (a version of Denis Beaubois’s earlier performance on surveillance) - the group creates a spectacle that draws the public’s attention to the presence of the unmarked police camera that watches them. In Amnesia, a disgruntled actor stands in the middle of Times Square holding large handwritten messages to the camera that include: “I HAVE AMNESIA,” “YOU HAVE BEEN WATCHING ME ALL DAY, EVERYWHERE I GO. MAYBE YOU CAN HELP ME.”

The last message is especially ironic because the police monitoring the camera will not help the amnesiac despite the fact that the function of the cameras is purportedly to ensure public safety. The SCP took action because they, like many other activists, saw the installation of unmarked cameras as an erosion of individuals' privacy.

The Surveillance Camera Players, “Who We Are & Why We’re Here,” 2001.

Although the group no longer performs on the street, its website, writings, and documentation live online to address issues around surveillance and privacy.

Although an undercurrent of activism characterizes surveillance performance art, artists like Meshi create works to investigate how the technology itself operates and sees. James Harding wrote, “find out how these technologies perform…and you’ll have a pretty good idea of whose interests they ultimately serve.”

James M. Harding, “Outperforming activism: reflections on the demise of the surveillance camera players,” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 11, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 141.

Indeed, Meshi’s Techno-Schizo exposes discriminatory biases within algorithms’ misclassifications. By making these design flaws in the coding apparent, Meshi calls attention to the need to modify and redesign the system.

In ZEN A.I., a collaboration with Treyden Chiaravalloti, Meshi makes visible the pervasive presence of surveillance technology via the algorithms that monitor and read her while she meditates in a room with smart devices surrounding her. The space she has constructed feels like a domestic/residential interior, a place that should be a refuge from the pervasive view of outsiders. Meshi’s ZEN A.I. illustrates Morrison’s summation of John McGrath’s argument that performance artists “re-create spaces which provoke audiences to experience rather than perceive or conceive of surveillance.”

Elise Morrison, Discipline and Desire, 11.

Performance uniquely prompts bodily and psychological reactions in viewers that make the work personal as well as conceptual.

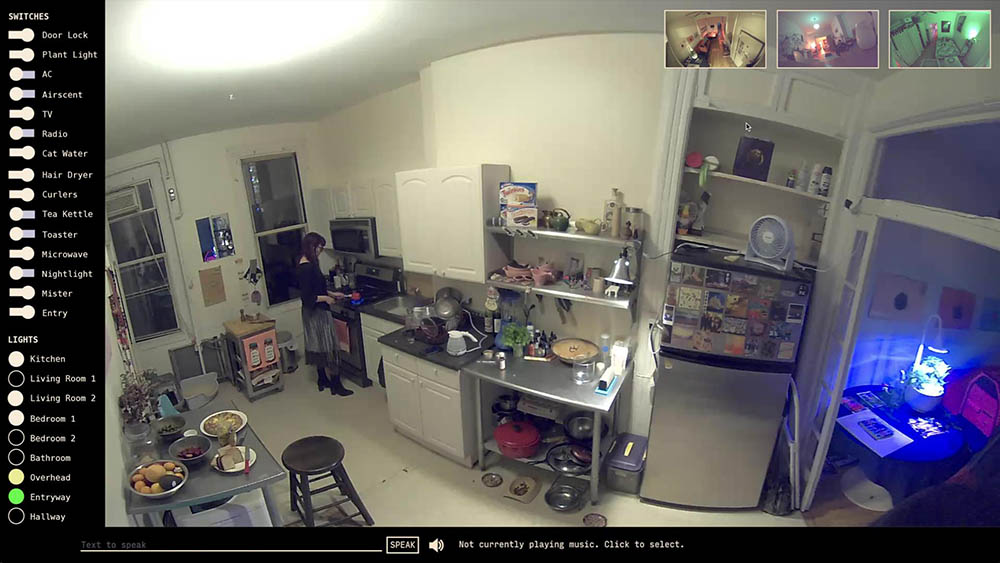

Lauren Lee McCarthy examines the relationships between humans as well as between humans and machines. She creates performances situated in the physical world that have real-life consequences, where both the performer and the audience must participate and become implicated in technological and social systems. Lauren Lee McCarthy, “Statement,” last accessed March 18, 2022.

For example, in LAUREN (2017-ongoing), she becomes an alternative to Amazon’s Alexa. She asks participants to invite her into their homes for a week and installs custom-designed smart devices that enable her to monitor the home’s inhabitants 24/7 remotely and control all aspects of their home just like Alexa. Through this performance, McCarthy embodies the machine, attempts to outperform the AI through her ability to connect on a personal level, and discovers the distance between the algorithm, herself, and the human users she serves. She investigates the tensions between intimacy and privacy, the smart home model's convenience and agency, and the role of human labor in the future of automation. Lauren Lee McCarthy, “Lauren,” last accessed March, 18, 2022.

In their TEDx talk, civil rights advocate Kade Crockford addresses how surveillance technology, especially facial surveillance, erodes people’s privacy and enables the state to create digital profiles that record people's movements and behavior—a digital panopticon. Kade Crockford, “What You Need to Know about Facial Surveillance,” TEDxCambridge Salon, 2019, Crockford also points out that it is not just large-scale surveillance technology that is of concern. Smart devices pose a risk as well. Brought into the home, they are susceptible to hacking, thus leaving the user exposed to personal risk. Through photographs, videos, and performances, surveillance artists make visible the pervasiveness of surveillance in modern society, revealing technology’s design flaws and biases, and calling forth the need to redesign surveillance systems that are inclusive and ethical.

In the wake of today’s ever-evolving surveillance society, surveillance artists have come to use the language of security against itself. By employing cameras, security footage, and (more recently) code and algorithms, they create work that raises awareness about state and commercial surveillance. They provide an important check in the balance of power between those commissioning such activity and those who would otherwise remain none the wiser.

Even more than creating awareness, artists often assume a position of power by turning the surveillance network onto itself, becoming, along with others like WikiLeaks and Cryptome, watchers of the watchmen. Indeed, works like Meshi’s Techno-Schizo embody the act of looking back at technology. While the algorithm reads Meshi, she has her eye on the output and adjusts her face in response, triggering classifications with varying levels of accuracy. Meshi engages in a delicate dance with this technology, creating a gray zone best contrasted with willful ignorance on one end and the deliberate destruction of surveillance systems on the other. In the space between, artists such as Meshi harness and re-deploy surveillance technology to create their work in an attempt to render visible the invisible.

Written by Alejandra López-Oliveros, Goldie Gross, and Janelle Miniter, curators of Avital Meshi: Subverting the Algorithmic Gaze. Essay designed by Jason Varone.